The split between Imperial ecology, which stresses human dominion over nature, and Arcadian ecology, which focuses on an interconnected, harmonious relationship with the natural world, has left a legacy of implications that stretch across the post-modern human-nature relationship. Aldo Leopold helped Arcadian ecology take root in the thought processes of American society by addressing the nature of the human relationship with land. He did this through his work and teaching, setting an example that has stayed at the forefront of environmental thought for decades. Leopold, in examining the impacts of agriculture on the soil, notes the way Americans have come to treat natural resources solely as a means of production. He strongly avers in The Land Ethic, “do we not already sing our love for and obligation to the land of the free and the home of the brave?”¹, but notes directly after how we do not extend this love, patriotism, or devotion to the biota surrounding and supporting us. He questioned in A Criticism of the Booster Spirit, if “growing away from the soil has spiritual as well as economic consequences which sometimes lead one to doubt whether … (the idea of) Americanism attaches itself to the country, or only to the living which we hook or crook extract from it.”² While discussions about apex predators’ importance in the food chain and colony collapse in bee populations are beginning to enter mainstream American conversation, there is a lack of awareness of the essential importance of soil. Understanding the reality that soil is a foundational component of life support is a critical step to changing public perception of conservation and protection measures here in the United States.

Leopold, a forester by vocation, was an avid conservationist who argued for a new ethical relationship with the land. Looking back through the lens of history, Leopold could see a natural progression in ethics which would grow to include a cooperative relationship with the entire biotic web. This new ethics would hinge on the Community Concept, the idea that individuals are members of an interdependent community², and that the health and success of that community is in the best interest of all involved individuals, human and non-human. In The Land Ethic, he drew attention to what he called the A-B Cleavage, with group A viewing land as the means of production and group B having a more gestalt view of land. Group B viewed the land as a living system with broad functions and purpose. Today, we still toe this divide.

Farming and agricultural practices in America lend themselves to high levels of soil degradation for the sake of quick profit. An NPR article from 2012 described an experiment on biodiversity conducted by David Littschwager. A one cubic foot hollow box was placed in various locations around the globe. The contents of life therein were measured and accounted for. It was a wonderful example of the range of living variation found in small spaces, of the way life proliferates and exists all around us and underfoot. In different locations they noted “30 different plants in that one square foot of grass, and roughly 70 different insects… 150 different plants and animals (passing through) in that one square foot of tree…”³ The diversity was beautiful. Then they took the cube to a cornfield where nothing could be heard save the rustling of cornstalks – literally, nothing. Nine insects and plants were found in the cube. No birds flew overhead. No bees buzzed around in the summer sky. Pesticides, herbicides, and potentially in this specific situation, GMO corn, had driven all other life forms from the soil. The air around the field was a no fly zone for anything living and non-human. Here, the land was treated as “biotic mechanism”¹. This current example of how agricultural practices are affecting the land is poignant. It highlights the intensity of the impact large scale agricultural production has on soil and ecosystem health.

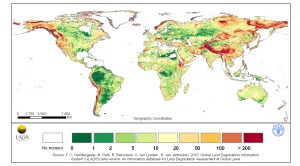

Soil degradation issues vary from ecosystem to ecosystem. Naturally, solutions vary as well. Global tropical deforestation for palm oil plantations has led to serious soil erosion issues as well as massive carbon releases into the atmosphere. Exercising best management practices (BMP’s) on existing plantations would go far to help tropical ecosystems recover from soil loss and its fallout. Here in Florida, the restoration of channelized waterways helps restore overland water flow. Planting native vegetation in the riparian buffer zone along these rivers and streams allows the land to retain both water and soil. The soil itself acts as a natural filter for the water by removing harmful impurities and replenishing the aquifer. Recent news articles have focused attention on the restoration of water flow via water releases along the Colorado River as the source of riverbank replenishment and healthy water levels. This provides critical habitat for wildlife, supporting the food chain. Dam removal is a practice moving to the forefront of environmentally sound practices here in the U.S. Water is part of the land, an essential part that carries and deposits soil at its rightful destinations. Allowing natural systems to do their job and being laissez-faire about the workings of natural systems may be one of the best lessons this generation is receiving from the environmental movement. The best way to tackle soil erosion at home is to plant native vegetation instead of lawn. This helps hold down soil and provides habitat for insects and animals indigenous to the area. Starting with a soil analysis to find out the health of your soil is highly recommended and can usually be done for free at your local Ag Extension.

Soil loss, degradation, and pollution are issues all over our country, driven by large scale agriculture and ranching. The Chesapeake Bay Foundation, a non-profit organization that focuses on the entire Chesapeake Bay watershed, does work to both raise awareness about ecological issues and employs conservation practices to heal the land and waters feeding into the bay. In one of their projects, they work directly with farmers in Pennsylvania under the state’s Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (CREP) to create buffers along streams on agricultural land by fortifying their banks with native plants and trees4. This vegetation holds soil in place, decreasing erosion and increasing water quality and flow. Fences create easements on stream and creek beds, keeping livestock out of the water. Reestablishing the riparian buffer zone further promotes soil stability and improves water quality by reducing fecal bacteria, pesticides, and herbicides released into streams from soil erosion. This is not an effort farmers have chosen to make on their own. It has taken an understanding from the state, the farmer, and an NGO of the long term effects of derelict land use practices on both the land and the water that is the lifeblood of our nation to begin steps toward healing. It is a community effort to change land ethics through the experience of the positive benefits of effective BMPs.

The Dust Bowl of the 1930’s was driven by poor land management practices. Farmers had turned up virgin topsoil and uprooted the native grasses of the prairies. When drought came, there was no natural biotic community able to withstand the lack of water and hold down the topsoil. Social and economic crisis ensued. The Everglades stand as another historical example of what happens under poor land management practices5. Once a natural flowing seasonal river, the Everglades gave rise to rich, organic soil. Canals were dug to divert water away from developing areas and to agricultural areas, creating a more stable hydrologic cycle. Affected by a negative view of wetlands, we dammed and bounded the water. As the soil dried, it sank. Subsidence has claimed over 6 feet of topsoil in the Everglades. Through these mistakes, and others, Leopold’s call to find our place among nature rather than above nature rings clear.

Leopold, fastidious and practical, taught us ways to live in working harmony with the land, using her resources and maintaining her overall health. This began a slow movement away from Imperialist ecology and the mechanistic mentality of production. Today we still struggle forward in this direction toward a more holistic, system inclusive relationship with the natural world. Our understanding of land use is growing, though we still endeavor to embrace concepts that increase soil fertility and health. These very land use practices, such as the example from the Chesapeake Bay Foundation of creating land buffers around streams and creeks, do more than increase the health and viability of the land. They are holistic in their very nature, creating cleaner waterways, producing healthier food, and maintaining a high level of aesthetics through the preservation of open green space. Holistic land use practices shore our society up against the inherent dangers in our monoculture system, allowing diversity to create a complex web of stability that fortifies the soil beneath our feet. Best management practices in the Everglades and in the Chesapeake Bay watershed are reducing soil erosion and improving water quality in quantifiable ways. They are setting examples of steps we can take to participate as citizens within our natural community, encouraging growth and health over mass production.

Article Sources:

¹Leopold, Aldo. “The Land Ethic.” A Sand County Almanac. New York: Oxford UP, 1966. Print.

² Oelschlaeger, Max. The Idea of Wilderness. New York: Yale UP, 1991. Print.

3Krulwich, Robert. “Cornstalks Everywhere But Nothing Else, Not Even A Bee.” NPR, 30 Nov. 2012. Web. 16 Oct. 2014. http://www.npr.org/blogs/krulwich/2012/11/29/166156242/cornstalks-everywhere-but-nothing-else-not-even-a-bee

4Chesapeake Bay Foundation. “Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program.”. 1 Jan. 2014. Web. 16 Oct. 2014. <http://www.cbf.org/how-we-save-the-bay/programs-initiatives/pennsylvania/susquehanna-watershed-restoration/crep-conservation-reserve-enhancement-program>.

5American Society of Agronomy. “Where has all the Soil Gone”. Science Daily, 18 June, 2014. Web. http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/06/140618163922.htm

Great read!

LikeLike